Relationship Reset: Apologies

In a previous post, I commented on a SciShow video that purported to talk about the relationship between knitting & physics.

Like many, I was underwhelmed (at best) and annoyed/angry (at worst) at the treatment that knitting received in that video.

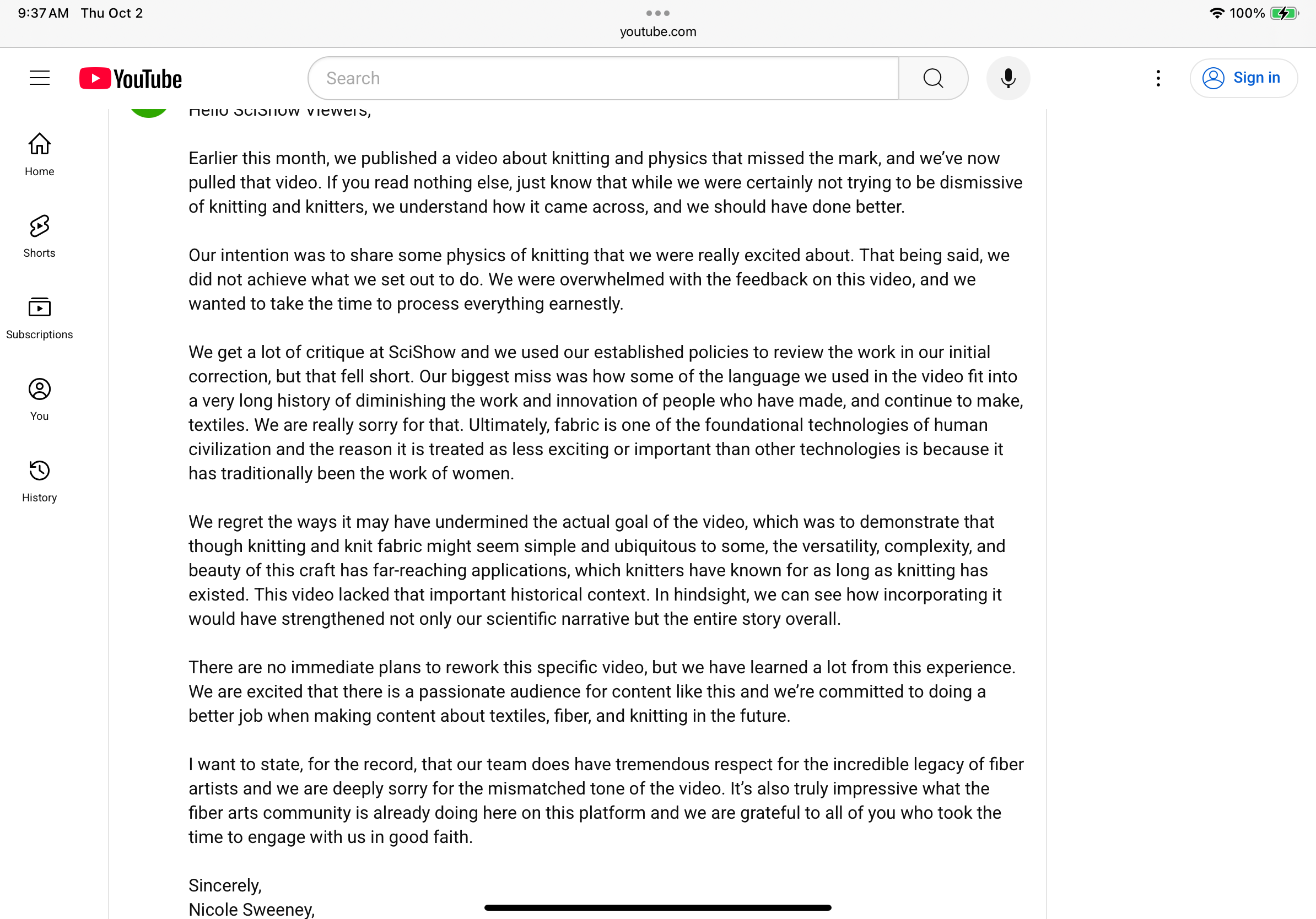

Two weeks—and many, many responses from the knitting community later—SciShow has decided to pull the video and offer an apology (Nicole Sweeney is an Executive Producer of SciShow):

This response got me thinking about the role—and importance—of apologies in relationships.

I think we all intuitively know that apologies help when people are hurt, but unfortunately, I think many of us have no clue what constitutes a “good” or “helpful” apology.

For example, SciShow initially attempted to remedy the issues caused by their video by offering a correction that also read as a quasi-apology/ defense of the original video.

It made many knitters more angry and annoyed than they previously were.

Who among us hasn’t been there? We thought we were doing something to make things better and… they ended up a bit worse.

One of the best books I’ve encountered about apologies is Harriet Lerner’s Why Won’t You Apologize? Healing Big Betrayals and Everyday Hurts (2017).

If you’ve ever experienced a relationship where you felt you should have been offered an apology, but weren’t, this book can help you understand why—and move on from it.

And if you’ve ever been in a relationship where an apology should have helped, but didn’t, this book can help you understand why—and move on from it.

As Lerner points out, “‘I’m sorry’ won’t cut it if it’s insincere, a quick way to get out of a difficult conversation, or followed by a justification or excuse” (1).

In particular, Lerner observes, “Almost any apology that begins with ‘I’m sorry if…’ is a non-apology” (18).

In the case of SciShow’s video, I think the initial effort to remedy the situation was sincere, but I do think it came across that they wanted it to go away (“a quick way to get out of a difficult conversation”), and it was most definitely followed by a justification (or two) and an excuse (or two).

I think the decision to pull the video and the apology that followed remedied both of these problems: as a result the sincerity comes across far more clearly (to me, at least).

As Lerner points out, in a sincere apology, “‘I’m sorry’ recognizes that the other person was put out or going through a difficult time, and we want to communicate that we care” (3).

Most importantly, Lerner notes, “The apology is the chance you get to establish the ground for future communication” (15).

I think this is what SciShow’s latest decision and statement demonstrate: that they care about their communication with knitters AND scientists, and that their video did not communicate that, and that they will need to figure out better ways of doing that moving forward.

As one of my friends once observed, “It’s amazing how a sincere apology really does make you feel better. It’s like a big hurt just… shrinks.”

Which leads me to a final observation about apologies: the issue of “forgiveness.”

Too often, people assume that if they apologize, they’re entitled to forgiveness.

This is a tricky one, because it depends on the nature of the harm inflicted.

For a minor infraction (I spilled juice on your carpet, for example, and I apologized and offered to pay to have it cleaned), withholding forgiveness suggests that the person harmed maybe has their eye a little too closely trained on the power dynamic in the relationship.

For a major infraction, however, it’s more complicated.

As Lerner points out, a “fine way to ruin an apology is to view your apology as an automatic ticket to forgiveness and redemption” (21).

In these cases, “it’s really about you and your need for reassurance”—not about what you actually did that hurt or harmed or betrayed the other person (21).

In the worst case scenario, people who expect—and receive— this kind of automatic forgiveness walk away knowing that they can “play” you.

Odds are, they will do what they did again… and again.

To you, and probably to others as well. (Cold comfort indeed.)

I have lived experience of this: a friendship I once had went sour for a time, but apologies were offered and we committed to working to repair it.

Almost immediately afterward, it began to slowly unravel again, thread by tenuous thread.

When I commented on this situation to a longtime friend, I lamented that the person had apologized, and I truly believed it was heartfelt and sincere, and I was committed to moving forward, but … it just wasn’t working and I couldn’t understand why.

My friend replied, “I know why. Because every time you have a conversation with the person, they sidle back up to one of the topics that caused the rift—or to a indirectly related topic—and then they say something that takes just a little piece of their apology back.”

Yeah.

If ever you want to destroy a friendship by inches, do that.

In the end, I simply gave up on the friendship because 1) life is too short, and 2) someone who exhibits that kind of overwhelming need for control in a relationship is emotionally exhausting (at best) and emotionally abusive (at worst).

One day I woke up and realized I just didn’t care anymore. There were no more pieces to put together.

They’d taken them all back and gone back to doing what they’d done before.

And I no longer felt compelled to go through it all again, because now I knew that any apology would just be a case of “second verse, same as the first.”

As Lerner notes, “A heartfelt apology is not about you”—it’s about the person to whom you’ve apologized (30).

If you apologize and then quickly shift to focusing on yourself, well… that apology probably won’t “take.”

That said, we all have different standards and thresholds when it comes to emotional connections: what works for me might not work for others.

In the case of the SciShow Knitting & Physics fiasco, I appreciated the decision to pull the video and offer an apology that strikes me as thoughtful and sincere.

It makes me more likely to watch their content in the future, because it gives me the sense that knitters were “heard”— that some understanding of why we were so angered and annoyed was achieved on the part of the SciShow team.

That kind of understanding and the commitment to communication that accompanies it is the stuff on which good relationships are founded.

So here’s hoping.