The “Brave” Professor

When I first read Paul Bloom’s September 24, 2025 article, “Why Aren’t Professors Braver?” in The Chronicle of Higher Education, I had a few immediate thoughts.

But then I thought, “Bite your tongue…”

But then I thought, “Well, he said to be braver, so…”

So here goes.

After all, I’m a retired professor now and, as Janis Joplin once sang, “Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose.”

A lyric which actually ties in quite nicely with my initial response to this question of professors and “bravery.”

Professors, as Bloom’s essay acknowledges, have something to lose when/ if they speak up to challenge their colleagues.

Personally, I think that “something” is far more nuanced than the idea that we’ve internalized the notion that “it’s bad to be disliked,” as Bloom suggests.

According to Bloom, “some academics really don’t like people who don’t share their political and moral views.” (As opposed to all the rest of the population, who embrace their fellow human beings on the other side of the political aisle?)

As a result, Bloom argues, professors are pressured to self-censor in order to protect themselves and advance in their careers.

Bloom also offers (& echoes) the argument of Noam Chomsky, “put crudely”:

“if you are the sort to say fuck you to your professors, refuse to do assignments that you see as stupid, or even push back in milder ways, you’re not going to get perfect grades and glowing recommendations. And so you’re unlikely to get into a top graduate program, which means you’re not likely to end up in academia.”

Bloom argues that, for those professors who are “brave” (“troublemakers”), it is likely that they

“got jobs and tenure before they got controversial” (“they made it in under the wire”)

hold jobs in “other parts of the university, like business schools and law schools, where there is more tolerance for troublemakers” and/or

“they are geniuses”

Two things stand out to me in this argument and its framework.

First, Bloom begins his essay with two paragraphs in which he insists on how wonderful professors are and how much he enjoys their company.

My immediate reaction to this was two-fold.

On the one hand, my snarky inner-adolescent wondered whether he perhaps worked at the university in “Brigadoon.”

My less-snarky inner child then innocently wondered why anyone would suggest that positive personality traits somehow align with one’s choice of a job.

Perhaps Bloom has had the good fortune to meet mostly nice people during his time in academia—people who would also be perfectly lovely co-workers if they’d been airline pilots or pet groomers or ice road truckers (I’ve been binge-watching—don’t judge me).

My point is, I personally try to avoid assuming that one’s choice of profession somehow signals how “likeable” they may be overall.

Because a lot of factors go into whether or not people opt to work in academia.

I also question whether the fact that Bloom seems to have felt the need to insist that he “likes” professors in general signals a certain nervousness about possibly offending all of these otherwise perfectly kind and generous and lovely colleagues.

If professors are all about being nice and likeable, surely they won’t care if you say something they don’t happen to like… right?

Oh, wait. No, that’s right—as Bloom himself acknowledges, “If 90 percent of the field adores you and 10 percent will describe you as ‘difficult,’ you’re likely screwed, career-wise.”

Which seems to suggest that the 10% who call someone “difficult” can sway everyone else to deny that person an opportunity to advance in their chosen profession.

I don’t like that. I don’t think it’s very nice, actually.

In his essay, Bloom at one point describes a scenario that he characterizes as an instance of “negative screening.”

Someone on a search committee “said something like, ‘I hear she’s difficult. Not really a good colleague” and so of course the committee “moved on to the next person, because we had a lot of names, so why waste our time on someone that we weren’t all enthusiastic about?”

“I hear she’s difficult.”

Oh—okay. NEXT.

Say what?

And yet, as Bloom asserts, as professors, we’ve all been in that committee meeting, and we’ve all heard that comment.

In my case, when faced with that question, I would always simply ask, “How so? What are you referencing?”

And yes, full disclosure, I was at times identified as “difficult” as a result.

To ask such questions is to be “braver” than many in academia—although I don’t really think it’s all that brave, quite frankly.

But here’s the thing: in academia, “difficult” (or “uncollegial”) is almost always a “criteria” invoked to either disqualify or hinder a female faculty member and/or a person of color from consideration and/or advancement.

Over the years, I’ve heard older white male professors described as “assertive.”

“Perhaps a bit arrogant.”

“An odd duck.”

“An old wind-bag.”

And—my favorite—”curmudgeonly.”

Behind the scenes, they might also be described by their colleagues as “sneaky,” or “predatory,” or any number of adjectives that go above and beyond the notion of simply being “difficult.”

But interestingly enough, they’re almost never publicly identified as “difficult”— and thus never denied advancement in academia.

Which gets me to what troubles me about Bloom’s article in general.

On the one hand, I think he’s describing the phenomenon known as “normative influence” or “normative social influence.”

A group’s collective norms, standards, and conventions—and the influence they exert on the members of that group—are by default shaped by the people who make up the collective group.

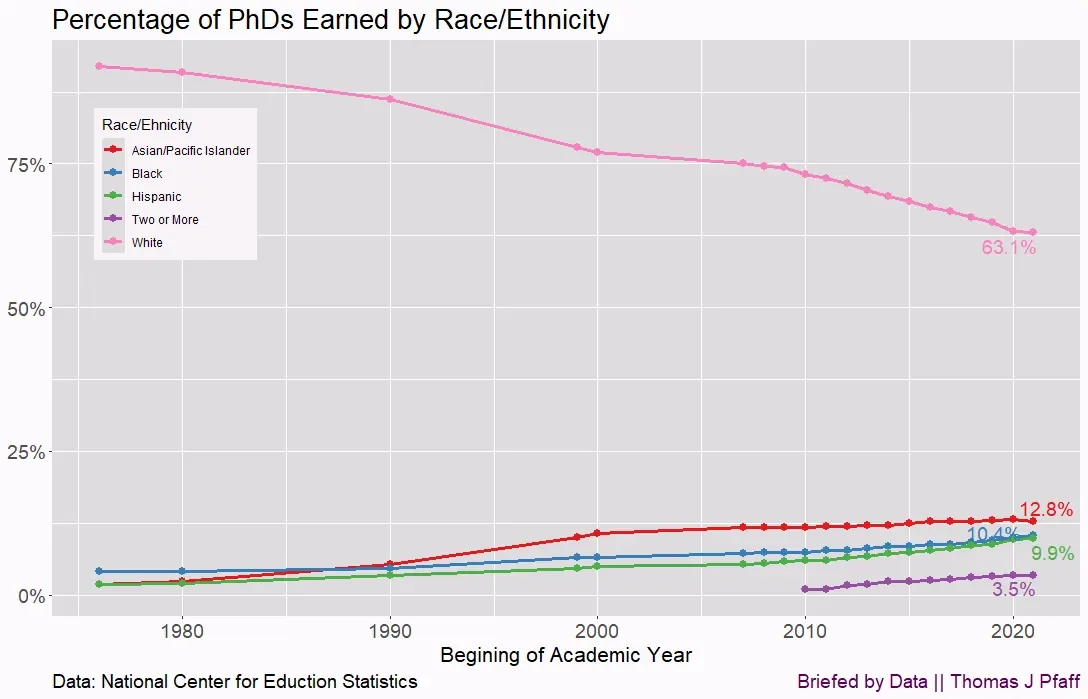

If you look at the percentage of Ph.D.’s earned by race/ethnicity, you’ll notice that, although their numbers have declined since the early 1970’s, the number of whites who earn Ph.D.’s in the United States has always far outpaced absolutely every other ethnic group—and continues to do so to this day.

Yes, the number of whites with Ph.D.’s has declined from over 80% to 63%, but the number of non-whites who earn Ph.D.’s has in no way, shape, or form risen proportionate to that decline.

Source: Thomas J. Pfaff, “Briefed by Data” https://briefedbydata.substack.com/p/college-faculty-by-race

The graph pictured above is drawn from data gathered by The National Center for Education Statistics.

When I look at this graph, personally, I think that any person of color who opts to pursue a career in academia is by default “braver” than many—if not most—of their colleagues, simply by virtue of their career choice itself.

They have to be.

I think Bloom’s notion of academic “bravery” dodges this issue by focusing instead on the idea of confronting “taboo topics”—the question of whether you should risk saying something that “will piss off” the “censurious minority” that characterizes the otherwise amiable cohort that makes up academia.

I would argue that there’s more to this issue of pissing of the censurious minority than the idea of being brave.

In the end, Bloom argues that “We should be more generous toward those with whom we disagree, more receptive to the possibility that they are right,” and—most importantly—”we should break the habit of punishing them.”

I agree. That would be nice. I think we would all like that.

But I also think that before we can do that, we’ll need to have broader conversations about what it means to be a professor in the United States—conversations that will need to be much “braver” than the ones we’re currently having.